Slavery and Gaming: Investigating a Tabby Slave Cabin Online Investigation

|

| A descendant of Easter Bartley, born enslaved at Kingsley Plantation, begins our investigation. |

This week cries of outrage and deserved disgust with a game called Playing History: Slave Trade 2 circulated around the internet, and I myself contributed by sharing the "Teachers and Gamers Agree: 'Slave Tetris' It's How You Educate Kids About Slavery" post from TakePart's digital magazine (and I'd do it again!). Slavery should not be the subject of a game, I immediately thought. As the day went on the the comments bounced back and forth, it seemed we all agreed this was a giant misstep but there exists the potential for thoughtful, well developed games on the subject. Why can't game developers work with archaeologists, historians, descendants, and interpreters to work out thoughtful ways to help students understand the lives of those enslaved? Why can't they show objects made and used by slaves to give a better understanding of what life on a plantation entailed? This game was from the slave traders perspective, why can't another game take the position of a family of enslaved people? Then today the thought hit me...

Wait, we already have a game that does this.

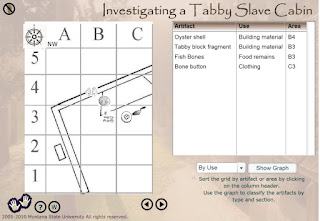

Only we don't call it a game. We call it an Online Investigation and it is one of the tools available for teachers and students who use our Project Archaeology: Investigating a Tabby Slave Cabin curriculum. (Note: this does not illustrate the Investigation in it's entirety but representative screen caps of the whole)

The Online Investigation is divided into 5 parts with various levels of interactivity. Part 1 "Meet Mrs. Deborah Bartley-Wallace..." is from the student handbook and includes images from the text. It also includes text on the environmental history of Fort George Island, flora and fauna in the estuary, and considers what building materials would be available to construct shelters.

The next section "History of tabby slave cabin" increases the interaction as students can take a closer look a historic photographs and primary resources related to slaves and their descendants. More background information from the student and teacher handbooks is provided with an emphasis on sacred traditions that reflect the slaves multiple African origins. Not to put it simply, the text describes different cultures and origins of the traditions from various locations in west Africa.

Then the investigation begins. In Part 3 of the Online piece, students must first understand site formation processes, how the footprint and postholes archaeologists find relate to a previously standing structure.

Then the footprint of a tabby slave cabin, a conglomerate based on authentic data from three cabins excavated by the University of Florida's summer field school directed by Dr. James Davidson, is divided into quadrants. The artifacts introduced in class are illustrated and their location appears on the planview of the cabin. Then each quadrant is presented as an opportunity for students to uncover (via hovering trowel cursor) the context of where the artifact was found. The data then appears to the right with artifact, number, and location recorded.

It isn't enough to just find things, the artifacts must related back to what they have learned about the lives of those enslaved at Kingsley, drawing from environmental and cultural factors learned over the 8 previous lessons. In this screen cap the focus is on blue beads and iron objects, moreover the context of where they are found adds to our understanding of perceived intentional placement and human behavior.

The interactive components drop off for the next section that discusses how NPS manages these delicate ruins, steps to preserve the standing and buried portions of the site, and when tied in with the classroom curriculum a very powerful conversation about the importance of descendants, importance of preserving archaeological sites, and why specifically preservation of sites of slavery are important to all of us.

Added for the Online and not as much a part of the in-class curriculum is Part 5, this measuring activity that has the students consider the greater plantation with attention to layout details.

The downside: very few people use the Online Investigation. Currently it is password protected an available only to those who have attended a Project Archaeology workshop or purchased Project Archaeology's Investigating Shelter guide on the Project Archaeology website. The curriculum itself (student and teacher handbooks) is free and posted on the NPS Timucuan Preserve website. Analytic data are not available but I would hazard to guess fewer than 100, if even 20 people have clicked on the site to use this feature of the curriculum. Half of the 20 would be me to take screen caps to share in workshops or blogs such as this one. I can't publish the password but if interested in viewing please contact me with a formal request.

In a recent poster presented at the Society for American Archaeology in San Francisco in celebration of 25 years of Project Archaeology, folks marveled at my fabric poster (it was fancy!) but what they didn't see was my clear confession that the Multiplier Effect of archaeologists teaching teachers to teach students is not working, at least not in Florida and not with the Investigating Shelter curriculum. This was my conclusion:

From a quantitative perspective, the “Multiplier Effect” (Selig 1991) of training teachers to teach students is not reaching its full potential in Florida. Very few teachers go on to use “Investigating a Tabby Slave Cabin” in the classroom, an issue compounded by data gaps given the difficulties in tracking teachers after the workshop. Also of concern is the number of active facilitators and that so few even within FPAN have gone on to hold independent workshops. Sustainability of the Florida program thus far depends on full-time employment, by FPAN or NPS, and the two graduates from the Leadership Academy [Sarah Bennett and Lianne Bennett] who have demonstrated tireless dedication at their own expense. The qualitative impacts are difficult to measure, but as an opportunity to raise the archaeological literacy of teachers and the educational literacy of archaeologists, the outcomes are worth the effort.Why is this important to gaming? To develop well-thought, sensitive, and educationally relevant materials it takes training teachers to use them, or at least how to present them to formal and informal audiences. Beyond Project Archaeology, I have yet to see our best developed "games" and resources be used to their full potential. These resources exist, but they are either not available broadly, widely, nor marketed in the "download the app now!" world we live in.

My raging questions from the day before are transformed. Yes we can teach students about slavery and help them understand components of this complex (and ongoing!) issue with sensitivity and understanding. What resources already exist that we are not using? Is it that the format is out of date? It is possible to transform these well developed Shelter investigations into a game format or app?

And finally, as some of you may be wondering, is the Online Investigation even a game? Parts of it are interactive. It's pretty spoon fed, but then it's based on authentic data and was never intended to be competitive with other players. I went down a wormhole trying to decide if it's a game, or interactive non-fiction, or interactive art (to join me in the wormhole see this discussion on Journey in the Guardian). It probably falls more solidly in the interactive website realm, but I'm stubbornly clinging to one of Merriam-Webster's definitions of game: a procedure or strategy for gaining an end. The Enduring Understanding of this lesson is: What can we learn about the history and lives of enslaved people by investigating a tabby cabin? Could it be argued that to meet our stated end the Online Investigation is indeed a game? One that helps teachers to engage students in understanding slavery through archaeological inquiry?

At least it's a start. If you know of another resource you can recommend, please post below. If you have an idea about how to recycle, reuse, or improve existing archaeology-based materials to develop appropriate games to aid in understanding slavery, please also post those ideas below.

Text: Sarah Miller, FPAN staff

Images: Online Investigation "Investigating a Tabby Slave Cabin" developed by Montana State University as part of a National Park Service grant. The Kingsley curriculum uses the Project Archaeology: Investigating Shelter template developed by Project Archaeology. The Kingsley Teacher Guide and Student Handbook was developed in true partnership with the National Park Service's Timucuan Ecological and Historical Preserve staff and Teacher-Ranger-Teachers (TRT), University of Florida's Dr. James Davidson, and staff including Amber Grafft-Weiss at the Florida Public Archaeology Network. Image credits can be found within the Investigation are are mostly attributed to NPS staff and archives, Dr. James Davidson, and Florida Memory Project.