Notes from the Trenches at Nombre de Dios, Update 11/1/19

We're excited to once again feature a very special guest blogger, Dr. Kathleen Deagan! She is back out at the Mission Nombre de Dios with more field work this fall. You can also check out the notes from last year's excavations to learn more.

We’re back at the Mission!

Excavations at the La Leche Shrine at Mission Nombre de Dios started a week ago. Our team includes Flagler College students and faculty, some seasoned archaeology veterans, and several dedicated volunteers of the St. Augustine Archaeological Association. Dr. Kathy Deagan and Dr. Greg Smith are leading the investigation.

And a big shout out to our financial supporters –

The Academy of American Franciscan History

The Division of Historical Resources, Florida Department of State, State of Florida

The Historic St. Augustine Research Institute at Flagler College

The Diocese of St. Augustine

Flagler College

The Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida

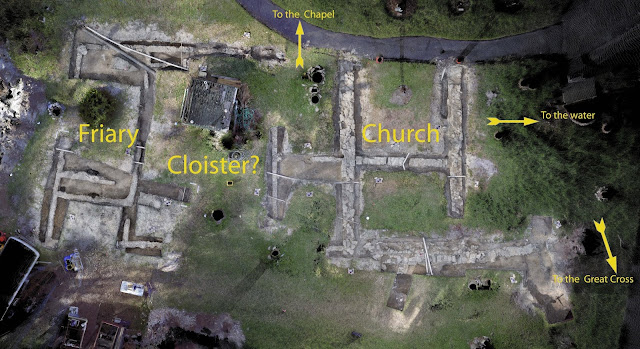

At the end of the 2018 season, Architect Marty Hylton and his team from the University of Florida EnVision program did photogrammetry and laser scanning of the site. For those of you who did not tune in last year, the site includes the coquina stone church built in 1678 as a shrine dedicated to Nuestra Señora de la Leche, and a friary built around 1706.

James Moore’s English and Yamasee troops captured and camped at the church during their raid of 1702, using it as a base to bombard St. Augustine. They destroyed as much as they could before retreating.

When the Spaniards rebuilt the Church around 1706, they added a friary built of tabby (a cement-like slurry of oyster shell, quicklime, sand and water). Two or three friars lived there, tending to the shrine church and the Native American and Spanish pilgrims who visited it.

The English captured the Shrine again in 1728, and the Spaniards decided that enough was enough, that the English were not going to have that chance again, and they blew up (literally) the Church and the friary themselves. But despite its tumultuous history, the site is a tidy 40-year time frame (1687-1728) for archaeology. And the footprints of the buildings survived.

That was a relief for us! We had mapped the wall foundations and feared that there might have been a mapping problem, since the buildings were not aligned. But the laser scanned image demonstrated that the friary building was, in fact, wonky.

So we still have at least three goals for this season

The team will be at the site until early in December, and we’ll try to provide weekly updates.

So far we have run into a few impediments (early 20th century concrete pathways, giant tree root systems, irrigation and sewer pipes everywhere), but the crew has it under control!

Click here to read the next update.

Words and images by Dr. Kathleen Deagan.

We’re back at the Mission!

Excavations at the La Leche Shrine at Mission Nombre de Dios started a week ago. Our team includes Flagler College students and faculty, some seasoned archaeology veterans, and several dedicated volunteers of the St. Augustine Archaeological Association. Dr. Kathy Deagan and Dr. Greg Smith are leading the investigation.

And a big shout out to our financial supporters –

The Academy of American Franciscan History

The Division of Historical Resources, Florida Department of State, State of Florida

The Historic St. Augustine Research Institute at Flagler College

The Diocese of St. Augustine

Flagler College

The Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida

At the end of the 2018 season, Architect Marty Hylton and his team from the University of Florida EnVision program did photogrammetry and laser scanning of the site. For those of you who did not tune in last year, the site includes the coquina stone church built in 1678 as a shrine dedicated to Nuestra Señora de la Leche, and a friary built around 1706.

James Moore’s English and Yamasee troops captured and camped at the church during their raid of 1702, using it as a base to bombard St. Augustine. They destroyed as much as they could before retreating.

When the Spaniards rebuilt the Church around 1706, they added a friary built of tabby (a cement-like slurry of oyster shell, quicklime, sand and water). Two or three friars lived there, tending to the shrine church and the Native American and Spanish pilgrims who visited it.

The English captured the Shrine again in 1728, and the Spaniards decided that enough was enough, that the English were not going to have that chance again, and they blew up (literally) the Church and the friary themselves. But despite its tumultuous history, the site is a tidy 40-year time frame (1687-1728) for archaeology. And the footprints of the buildings survived.

|

| Laser-scan and photogrammetric image produced by EnVision, University of Florida. |

That was a relief for us! We had mapped the wall foundations and feared that there might have been a mapping problem, since the buildings were not aligned. But the laser scanned image demonstrated that the friary building was, in fact, wonky.

|

| Archaeological map of the foundations. |

So we still have at least three goals for this season

- What is along the interior walls of the Church- particularly in locations that might have been raised platforms, altars, or baptistries?

- What was going on in the space between the friary and the Church? Was there a cloister between them? Was there an interior patio?

- Was the southern wall – which we believe was the principal entrance – made with an elaborate façade? At the end of 2018, we found a stepped entrance and evidence for large posts or pillars in one area, and we plan to find out if it was all along the façade.

| |

| The south wall of the church, showing steps with exterior plaster. |

So far we have run into a few impediments (early 20th century concrete pathways, giant tree root systems, irrigation and sewer pipes everywhere), but the crew has it under control!

Click here to read the next update.

Words and images by Dr. Kathleen Deagan.